Airbrake Module for High Powered Rocket

System Modules

Adaptive Airbrake Control System for High-Power Rocketry

Spaceport America Cup 2023 | University of Maryland Terrapin Rocket Team

Project Overview

As a member of the University of Maryland's Terrapin Rocket Team, I played a key role in the design, development, and testing of an active airbrake system for our high-power rocket, Karkinos, which competed at the 2023 Spaceport America Cup. My contributions spanned control algorithm development, systems integration, and ground support tooling - combining real-time embedded systems programming with aerospace control theory to create a precision guidance system capable of operating at supersonic speeds.

The airbrake system aimed to maximize our competition score by minimizing apogee error - the difference between our target altitude and actual peak altitude. Given the inherent uncertainties in rocket flight (wind gusts, motor performance variability from our student-researched-and-designed motor, and atmospheric conditions), an active control system offered substantial advantages over passive trajectory prediction alone.

Model Predictive Control Algorithm

My primary technical contribution was designing, programming, and testing the Model Predictive Control (MPC) algorithm that determined optimal airbrake deployment angles in real-time. The fundamental challenge was computationally intensive: given the rocket's current state (position, velocity, orientation), what airbrake angle would cause the vehicle to coast to exactly the target apogee - and how could this be calculated fast enough to maintain a 50 Hz control loop?

The MPC architecture I developed employed a binary search optimization method that achieved remarkable computational efficiency. At each 20-millisecond control cycle, the algorithm:

- Received current state estimates from the Kalman filter (height, velocity, tilt angle)

- Executed a binary search across the airbrake deployment range (0° to 90°)

- For each candidate angle, ran a forward trajectory simulation from the current state to predicted apogee

- Identified the deployment angle that brought the predicted apogee closest to the target altitude

- Commanded the airbrake mechanism to that optimal position

The binary search approach proved ideal for this application. Rather than evaluating all possible deployment angles or using gradient-based optimization (which could be unstable with noisy sensor data), binary search guaranteed convergence while minimizing the number of expensive trajectory simulations required. Through careful optimization of the simulation code, I achieved convergence times measured in microseconds - easily meeting the real-time requirements of the 50 Hz control loop with computational headroom to spare.

The algorithm converged to within 2-5 degrees of the optimal angle, providing sufficient precision for apogee control while maintaining the speed necessary for real-time operation on our embedded flight computer. Key implementation challenges included handling edge cases where no deployment angle could achieve the target (rocket already committed to overshooting or undershooting), managing rapid state changes during transonic flight, and ensuring numerical stability during the iterative simulations.

Systems Integration and Collaboration

A critical aspect of the project was integrating my control algorithm with the broader avionics system. I worked closely with teammates developing the Kalman filter to ensure seamless data flow between sensor fusion and control. The Kalman filter combined data from barometric pressure sensors, accelerometers, and gyroscopes to produce optimal state estimates, which my MPC algorithm consumed to make control decisions.

This collaboration became especially important when we discovered barometric sensor errors during flight testing. When the airbrakes deployed at high speeds approaching Mach 1, the aerodynamic disruption created local pressure variations that caused altitude measurement errors of 50-200 meters - potentially catastrophic for precision control.

Barometric Sensor Error Characterization

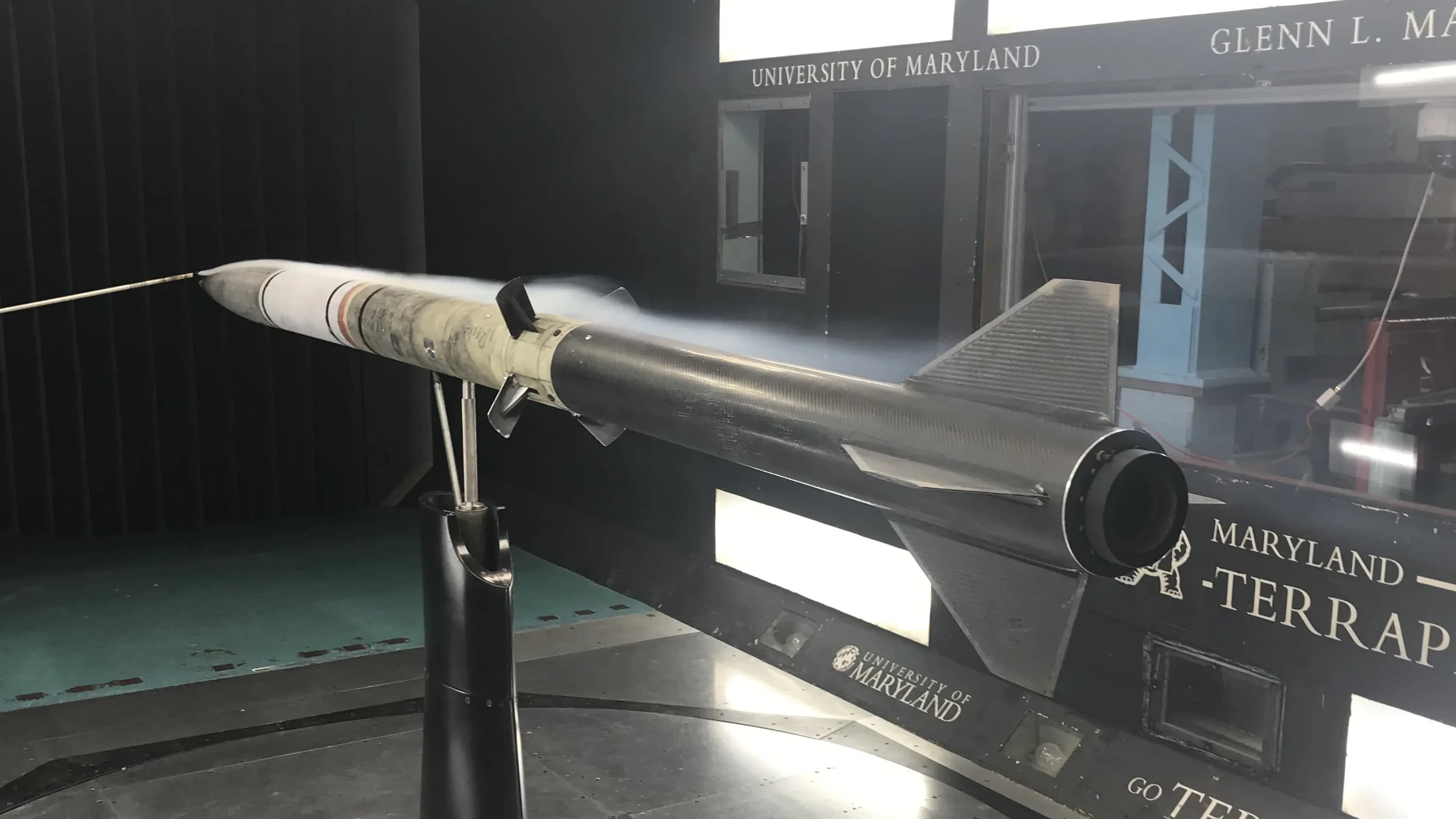

To address this challenge, I participated in systematic wind tunnel testing at the University of Maryland's Glenn L. Martin Wind Tunnel. We tested Karkinos across a comprehensive matrix of airspeeds (30-85 m/s) and deployment angles (0-90°), collecting data that mapped the relationship between flight conditions and sensor error.

I then contributed to the data analysis effort that produced a physics-based correction model. Through careful examination of the wind tunnel data, we recognized that the error correlated with dynamic pressure and deployment angle. We developed an error correction function of the form f(h,v,δ) = cq sin(δ), where q represents dynamic pressure. Linear regression yielded a coefficient of c = 0.052 with an R² of 0.97, demonstrating excellent model fidelity.

To handle transient effects during rapid airbrake movements, we implemented a time-dependent low-pass filter that gradually introduced the correction term. This prevented overcorrection during deployment changes while still providing accurate steady-state measurements. The corrected altitude measurements fed into the Kalman filter, which then provided my control algorithm with dramatically improved state estimates - a perfect example of interdisciplinary collaboration improving overall system performance.

Ground Support Infrastructure

Beyond the flight software, I developed ground support tooling to facilitate testing and development. I created a ground station application that provided an intuitive user interface for viewing downlinked telemetry data during ground tests. This tool proved invaluable for debugging control behavior, validating sensor readings, and monitoring system health during our extensive test campaign leading up to competition.

The ground station displayed real-time plots of altitude, velocity, predicted apogee, airbrake commands, and sensor health indicators. This visibility into system state allowed the team to quickly identify issues, validate algorithm performance, and build confidence in the flight software before committing to launch.

Competition Experience and Results

The Spaceport America Cup presented an unexpected challenge that tested our system's robustness. After idling on the launch pad in the New Mexico desert heat for several hours, a commercial off-the-shelf motor controller component overheated. During flight, the airbrake mechanism failed to physically actuate despite receiving commands from the flight computer.

However, post-flight data analysis revealed that my control algorithm continued to execute flawlessly throughout the flight, processing sensor data at 50 Hz and calculating appropriate deployment angles in real-time. The mechanical actuation failure was entirely independent of the control logic, and the telemetry confirmed that the software was generating correct commands based on the vehicle state.

In test flights prior to the competition, the integrated system had demonstrated excellent performance, achieving apogee errors as low as 74 feet (22.5 meters) - a testament to the effectiveness of the MPC algorithm, sensor error correction, and overall system integration.

Technical Presentation

I subsequently presented this work at an AIAA technical conference, focusing on two primary contributions: the binary search MPC architecture and its real-time performance characteristics, and the barometric sensor error characterization and data-driven correction methodology. The presentation emphasized how high-performance control systems require careful attention to sensor physics and how data-driven approaches can effectively compensate for complex aerodynamic phenomena.

Project Impact and Lessons Learned

This project exemplified the integration of multiple engineering disciplines - control theory, real-time embedded systems, experimental aerodynamics, data-driven modeling, and human-computer interface design - to solve a complex aerospace challenge. The experience reinforced several key lessons: the importance of computational efficiency in real-time systems, the value of systematic experimental characterization when dealing with sensor anomalies, the necessity of robust ground support tools for complex system development, and the critical need to consider environmental factors (like thermal management) in competition scenarios.

The microsecond-level execution time I achieved in the control algorithm demonstrated that sophisticated optimization methods can run on resource-constrained embedded platforms when carefully implemented. The successful characterization and correction of barometric sensor errors showed the power of combining first-principles physics understanding with empirical data analysis. And the competition day failure, while disappointing, validated our software architecture's reliability and highlighted the importance of thermal considerations in avionics design - lessons that continue to inform my engineering approach.